- Horst Kiechle, 2020 vPattern Basket

- Horst Kiechle, 2020 vPattern Basket

- Horst Kiechle, 2020 vPattern Basket

- Horst Kiechle, 2020 vPattern Basket

- Horst Kiechle, 2020 vPattern Basket

- Horst Kiechle, 2020 vPattern Basket

- Horst Kiechle, 2020 vPattern Basket

Selected by Garland contributor Gary Warner, our July laurel goes to Horst Kiechle for his constructed paper object 2020 vPattern Basket.

Gary writes:

Horst is an artist with a German engineering degree and an Australian MFA. Since the mid-1990s he has been making complex paper and cardboard objects using a combination of digital 3D modelling, self-written computer code, printing and meticulous making by hand. I vividly recall being enthralled by his ambitious transformation of a Melbourne gallery in 1996, lining it end to end with cardboard polygons to create the sense of a subterranean cave network (at least that’s how it felt to me). It was an exciting glimpse of future architectural possibilities beyond the rectilinear. Melbourne’s extraordinary Federation Square by Lab Architecture is an epic example of those possibilities.

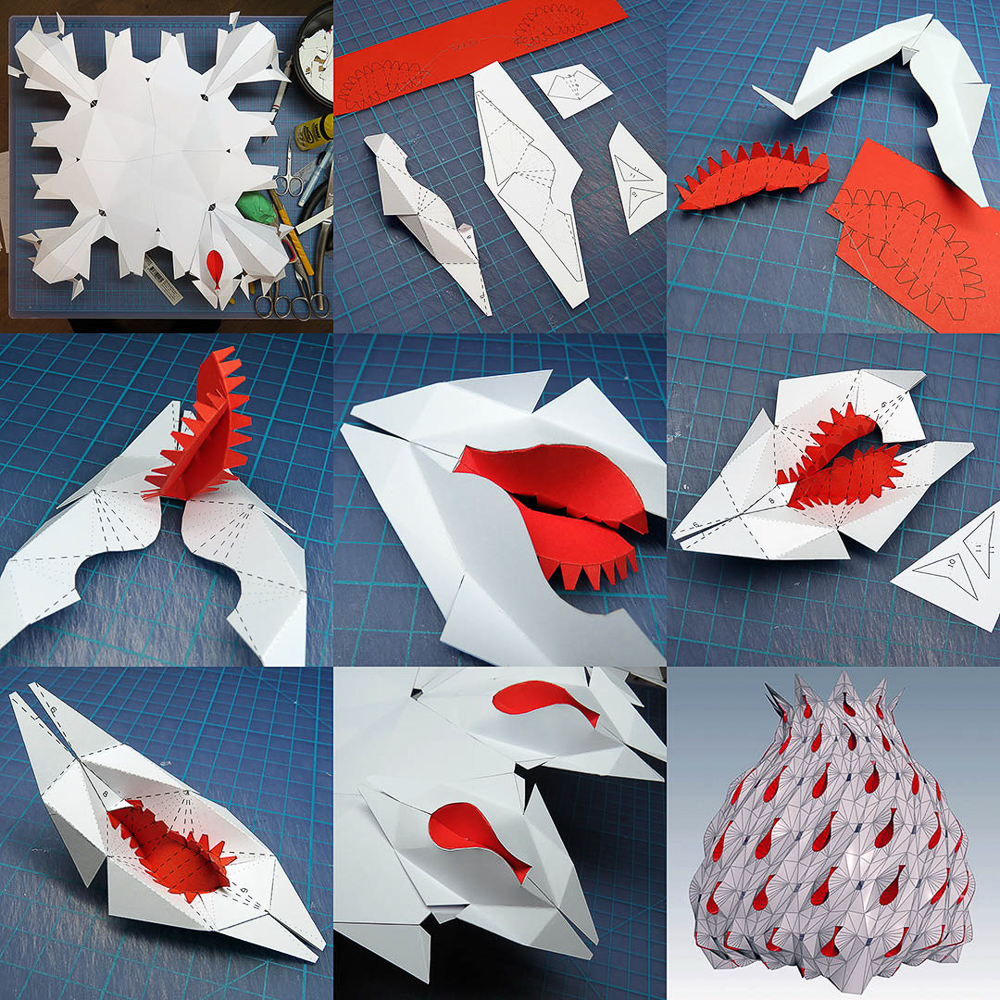

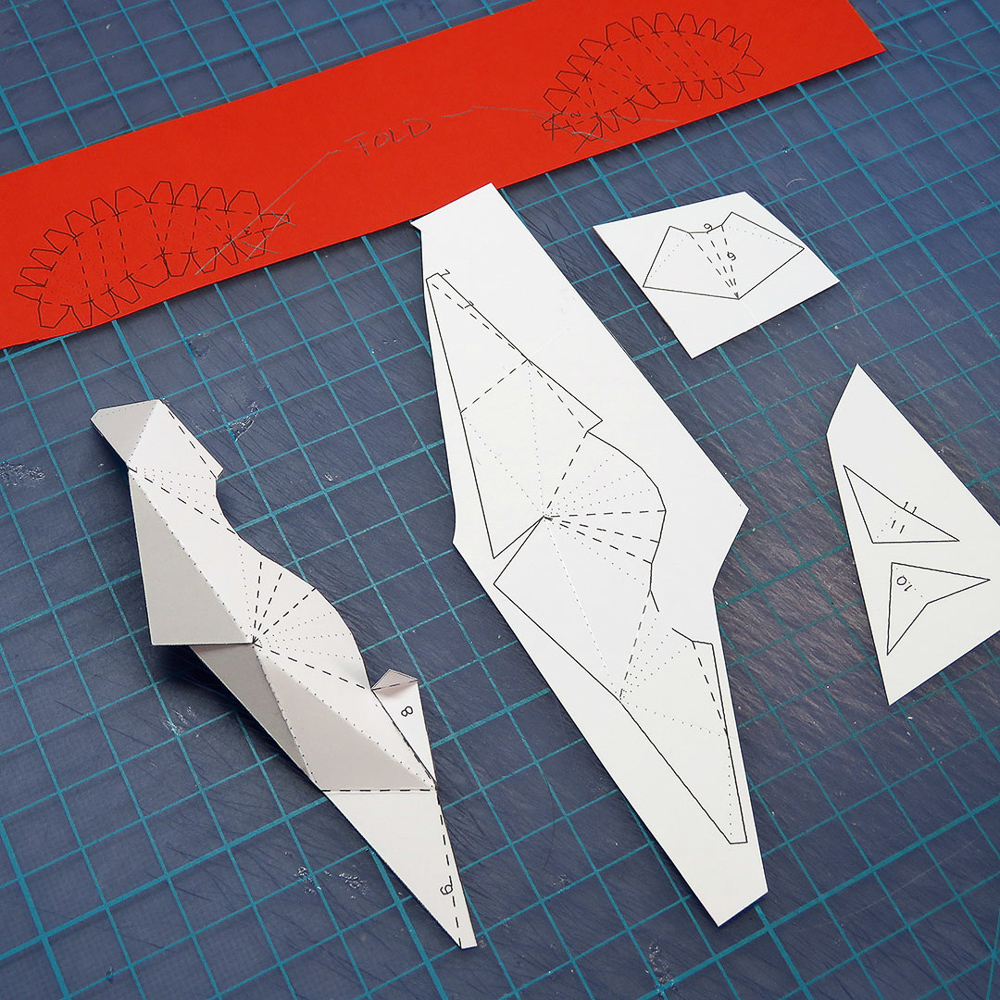

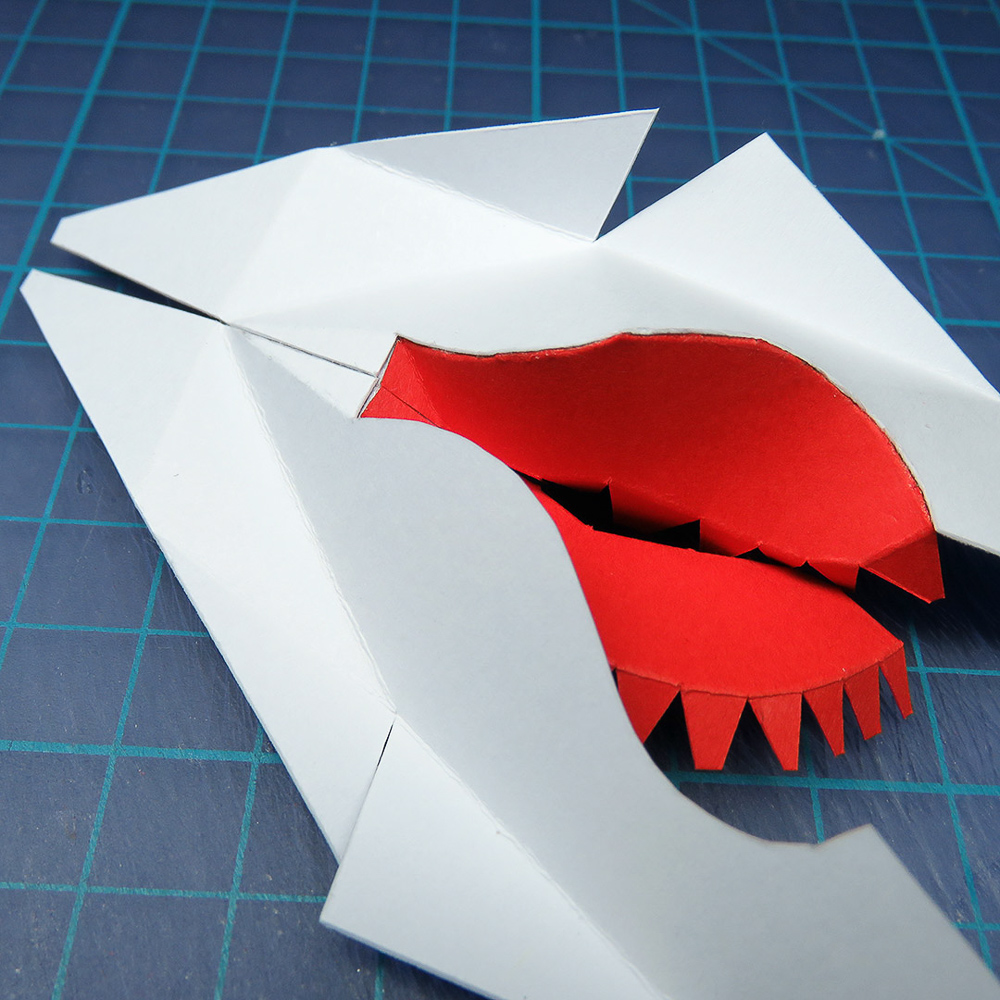

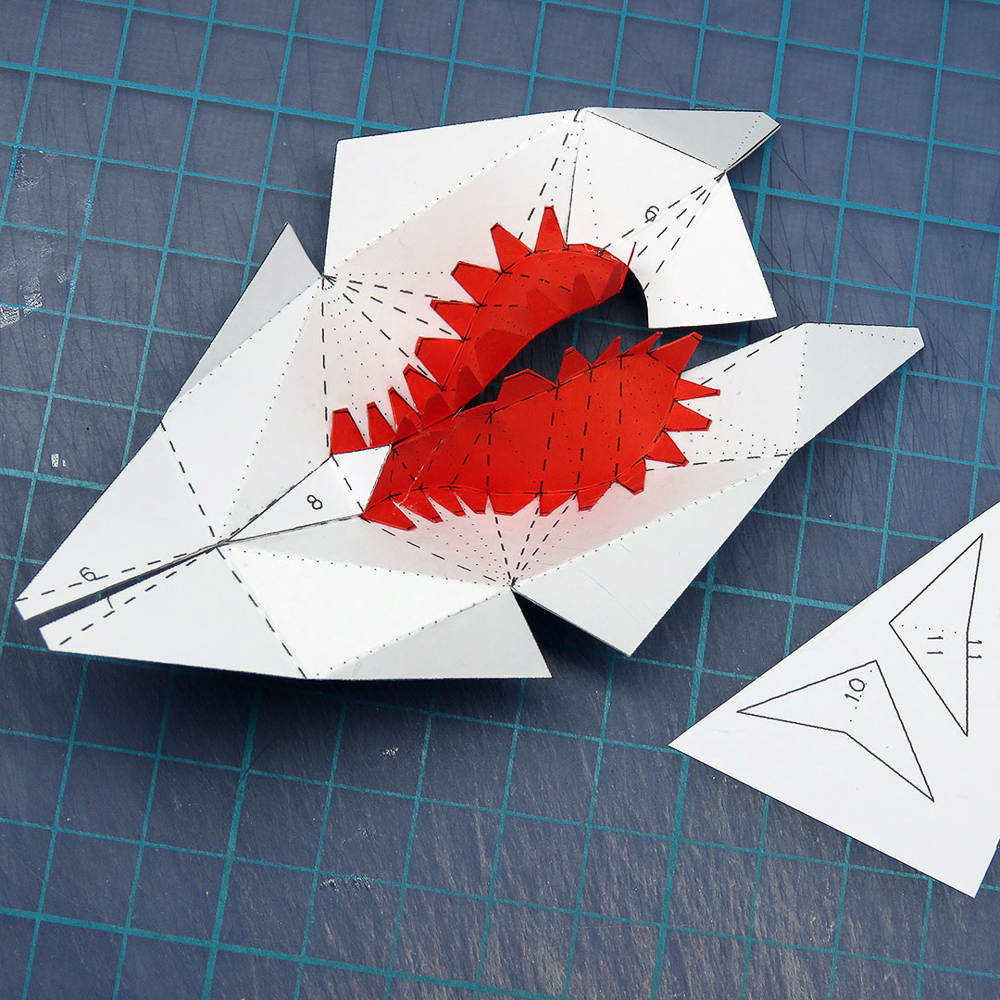

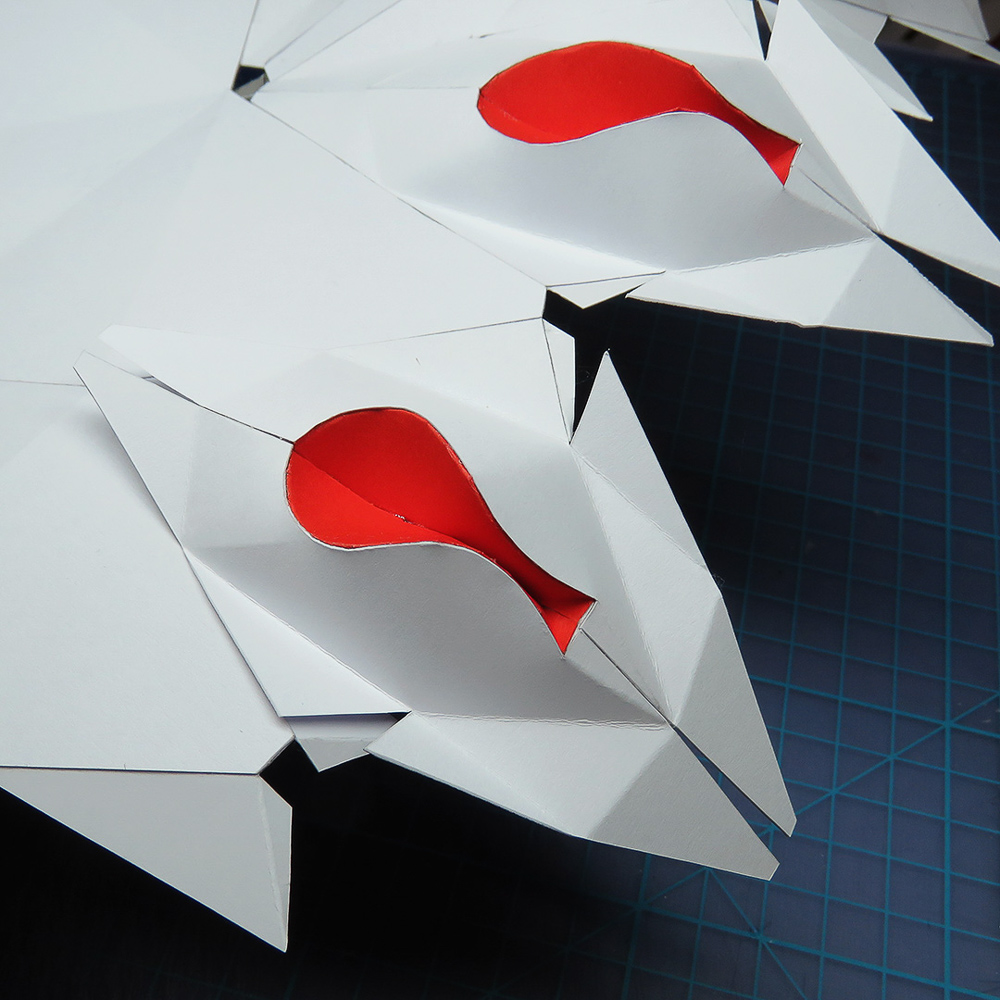

2020 vPattern Basket is a stunning recent construction by Horst comprising 99 similar yet non-identical unit elements and their paper connectors. Each unit was first developed in digital software, then printed onto a selected weight, colour and texture of paper to be cut, folded and glued by hand.

Horst’s projects are experiments in paper engineering that often require innovative structural solutions to problems which only become apparent in the making of the object. He likens the meditative and attentive frame of mind required for the long careful process of cutting, folding and gluing the paper units to doing needlepoint or knitting.

Horst explains his background and process:

Through my engineering degree in Germany I came into contact with computers very early on.I saw their potential for changing the way we design and produce things.

During my studies for a Masters of Fine Arts in Sydney I researched new computer-based design tools and their potential for an innovative architecture – away from standardised rectilinear boxes towards freeform shapes composed of unique elements. At the time I used large scale cardboard mock-ups to transform galleries and enable visitors to experience these unusual spaces by immersing themselves in them.

Moving to Asia I lost access to the equipment necessary for large scale installation projects and I developed an artistic practice that I could do from home—a hotel room even—consisting of laptop, portable printer, paper, scalpel and glue. In addition to working from home I also started to value a ‘balanced’ work process, ie. working with my hands for half the day (papercraft), something structured (developing my own software) and finally some creative time (designing new projects).

My appreciation for crafts started during my years living in Thailand, Bali and Fiji – by becoming aware of crafts’ potential to be produced and appreciated by a much larger proportion of the population than the more elitist ‘high art’ or architecture.

Weaving in particular caught my attention as it is a wonderfully simple and economical way to generate curved surfaces that most architects would have difficulty to design, let alone build. In Thailand I fell in love with a woven basket—square base gradually morphing into a circular opening at the top—which I used to develop a “digital weaving” process and the shape of the vPattern Basket is also loosely based on it.

More than 30 years after completing my engineering degree computer-aided design and manufacturing has enabled some exciting new developments in architecture. And I am certain that the use of computers can enrich some of the traditional crafts and possibly develop entirely new practices.

—- about ‘digital weaving’ —-

In traditional weaving, the material has a constant cross-section and the gaps between the material change to generate a curved surface. In the digital age it is possible to generate curvature by varying the width of the material and thus to make a ‘watertight’ weave of a curved surface or add gaps for ornamental reasons.

—- irregularity —-

In traditional manufacturing, designers would use standardised elements to minimise cost. In the digital age, it is possible to design with self-similar elements. No two the same at no increase in cost. Each element being different introduces a subtle irregularity akin to natural objects or craft.

Horst Kiechle, workshop

You can see more of Horst’s work on instagram @horstkiechle