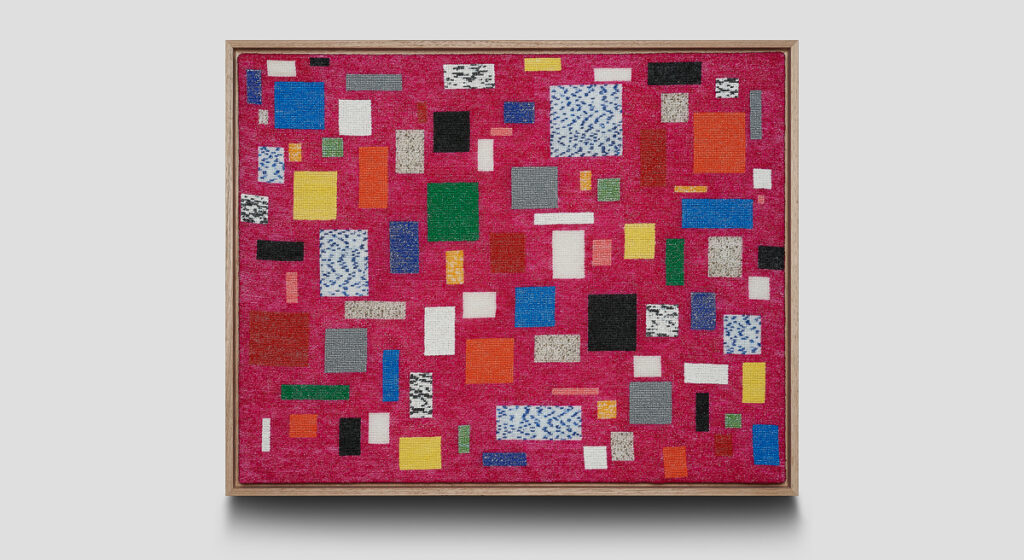

- Peta Kruger, Used (series), 2019-20, needlepoint found plastics on twist canvas, 585 x 740 mm. Photo: Sam Roberts.

- Peta Kruger, Used (series), 2019. needlepoint found plastics on twist canvas, 340 x 250 mm. Photo: Sam Roberts.

- Peta Kruger, Used (series), 2019-20, needlepoint found plastics on twist canvas, 480 x 330 mm. Photo: Sam Roberts.

As an act of creative resistance, Peta Kruger processes ugly plastic into fine weavings.

Inspiration

I made jewellery for ten years and during this time I found that naturally beautiful materials such as silver, gold and gemstones could be turned into equally beautiful wearable objects with relative ease. So I set myself a new challenge: to try to craft beauty from something quite hideous, namely waste plastic.

As a consumer, I try to avoid purchases that negatively impact the environment, animals or other people. This has meant eschewing products that contain palm oil, certain chemicals and animal-derived and tested ingredients. It has been extremely difficult, however, to eliminate soft plastics entirely from our household, and to ethically dispose of the material thereafter. Frustratingly, solutions to the waste plastic crisis are not immediate or apparent.

I was alarmed to learn that the conscious act of using degradable alternatives is worse for the environment than the impact of plastic in landfill. I learnt recently that the oxo-degradable plastic bags (such as black dog waste bags provided in council parklands) are not ‘environmentally-friendly’ as stated on their label. Oxo-degradable plastic is a technology designed to break down the material into tiny microparticles. Unfortunately, the plastic particles do not actually disappear and when they become very small they are then more easily absorbed into food chains and ecosystems.

The ‘plastic bag ban’ across supermarkets in Australia has proven to reduce plastic waste, but the instated system of replacing lightweight plastic bags with heavy-duty plastic bags appears altogether contradictory and the slow rate of progress in this area causes me great distress and sadness. After a decade-long career in the arts, I feel painfully inadequate and irritated by the lack of financial and technological resources I own to fight this issue. And so I have turned to my work in search of solutions, and in doing so brought a greater sense of urgency and renewed energy to my practice. Artists can engage critically, reflexively and agilely with complex issues, drawing on the past to make connections in the present. It was this process that led me to needlepoint works made from discarded plastic.

Materials

The plastics in this exhibition are sourced from food packaging, gift-wrapping, litter and occasionally dumpster diving. My neighbourhood has become a place where I can mine new material; a walk through the city is like a treasure hunt, and picking up litter in a playground helps to maintain my engagement with studio practice while I am looking after my son.

Collected plastic is sorted into colour groups, sanitised and then cut into strips for threading. The texture and thickness of each plastic dictate any further preparation that may be required. Every scrap of plastic thread created during the stitching process is also kept for recycling and weaving into future artworks.

Gift wrapping twine collected from birthday parties and playgrounds.

Sanitised plastic bags drying on clothesline.

Sanitised and drying after a chase on a main road.

Making process

Plastic is an inherently unattractive material. It is sticky to touch and it tangles, stretches, creases and tears easily. The most difficult aspect to overcome is its ubiquity and association with litter and waste. Its wide spectrum of colours, however, excited my interest and forced me to find a means of incorporating the material in my ongoing practice.

After three years of technical research, experimentation, walking away from the material and returning to it, I began to embroider with the plastic using the technique called needlepoint. Needlepoint stitching is a labour-intensive process. I calculated that it takes approximately 1 hour to complete 250 stitches. The largest artwork in the exhibition consists of 105,000 stitches, taking approximately 420 hours to complete over a period of four months.

The canvas grid condenses the volume of plastic waste and brings order to chaos. Every stitch is accompanied by a maddening awareness of the futility of my mission, and of the broader strategies currently in place to help protect the environment. And yet I feel compelled to persist.

The labour of stitching exhausts my body and concentrates my mind to a point where new insights are revealed. As I work across the canvas I begin to see new stories emerge as I place one piece of plastic alongside another. My personal story of consumerism becomes more complicated once intertwined with waste donated by friends and family, and collected from my neighbourhood.

Rather than rely on shock tactics, the work uses subtlety and persistence to carry an environmental message. It draws people close to examine the handwork and from this vantage point, they can begin to engage with the piece and trace my personal journey of reflection, atonement and commitment to the issue of plastic. The legacy of plastic is a story that will unfold for generations. For that reason, it seems prudent to consider and carefully organise this material for future readings, according it the status of a finely woven historic tapestry.

The jewel-like surface of the needlepoint helps to disguise the familiar and repellent properties of soft plastic. The source material is only revealed to the viewer upon closer inspection of the artwork and accompanying description, and it is always a joy to witness this realisation in those who have previewed the work.

The artworks present a complex and poetic layering of cultural and historical references, evocative of the ‘make do and mend’ ethos but with a revised, dystopian edge. Threading plastic onto canvas symbolises an adaptive human approach and each thread recalls the site (and accompanying stories) from which it was collected. Gathering, threading and stitching the plastic reminds me of a bird nest found recently in my backyard that was almost entirely constructed from synthetic materials, such as acrylic wadding and shade-cloth netting. It was a tragic piece of evidence and reminder of the Anthropocene, an era of significant human impact on the environment.

Soft plastics are imbued with new value through this process; litter has become an alluring colour palette and remnant scraps are kept like precious metal filings. Plastic once destined for stormwater and landfill is redirected to a gallery as treasure. Reinstating the plastic waste back into households is ultimately my goal.

Peta Kruger: Used, Jam Factory (Adelaide, Australia), 2 October – 22 November 2020