In the exhibition Expressive Repair, Lela Kulkarni finds Miron Kiselev, who helps translate graffiti to textiles.

“I love the stains on my shirt,” said Miron Kiselev. His skateboard sat beside him and leaned against his metal chair as if the skateboard were a dog or a close companion. His hair was tucked away from his face in a curly bun. And he sat in the sun so the small stains on his sweatpants and graphic-T could be seen in their full glory, “When I look at a ketchup stain I remember the hot dog I had and where I was at the time. A stain has history and memory.”

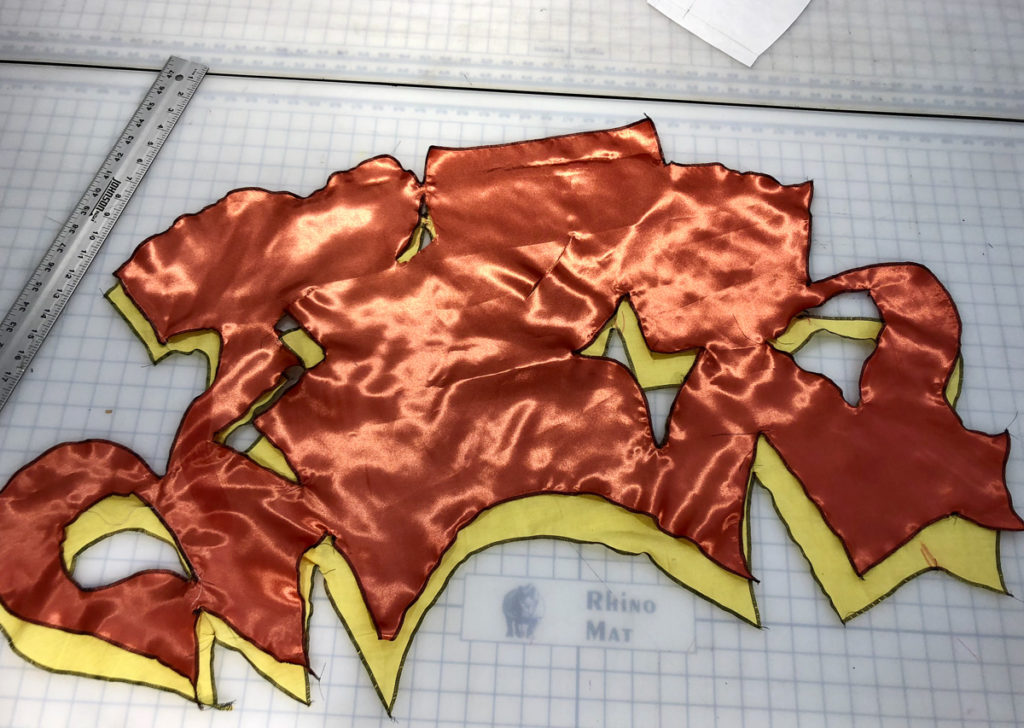

From his stains and patches to his graffiti, Miron Kiselev might seem like a grandmother’s worst nightmare; but that’s not what Miron is about. In the spring of 2019 at the RISD Museum’s Expressive Repair exhibit, the graffiti artist taught museum-goers about the philosophy behind modern graffiti and how this applies to sewing. Easy-to-find in his neon construction vest, Kiselev showed anyone who approached him (from senior citizens to elementary-school children) how to stitch, cut fabric in patches, and to make whatever creation they could with whatever scraps were around. As his fingers and the fingers of his students moved with the push and pull of the needle, he explained what it’s like for him to mark an abandoned space with spray-paint. He’d do things like pick up a piece of cloth he “tagged” (a minimalist marking or signature) and show how he put everything he learnt about graffiti into the cloth.

Because you cannot erase wet paint and it’s risky to return to the space, graffiti is carefully planned. The writers (what graffiti artists call themselves) must choose a location where the graffiti is unlikely to be washed. An example of such a place might be a wall that has only train tracks going by it. Writers want to have “runners” (pieces that last a long time). Then there’s the details of making the art itself. Time is spent on the shape of each letter and how they intersect. This process is called outlining, a stage which Kiselev isolated in his sewing and made examples of just outlines. In a way, the outlining process is similar to tagging. An outline is minimalist and through this minimalism, a letter is converted into an expressive signature, usually a style that’s impossible for another person to mimic. When a piece is a copy, graffiti artists can tell that the copier didn’t understand how the letters, the form and shape comes together. In this way, it’s like each artist has their own code for connecting the letters. It’s not an easy code to crack, and though some fashion houses have tried to do bags with so-called graffiti prints on them, Kiselev says, “It was the worst graffiti I’ve ever seen. They have no idea how it works.”

Once the base is done (or the outline is made and coded), the “fill-in” begins. “Fill-in,” as its name makes clear, is when the letters get filled in with color. What makes the fill-in complicated is using spray paint. Think of a can of spray paint. It doesn’t stroke at countless different angles like a paint brush. To fill-in the letters with color, the artist primarily go from left to right, right to left, left to right. Kiselev calls this process “printing.” Again, Kiselev does embroidery that highlights this phase. He call the fill in part “a dance” in which his hands “fully mimic that hand movement of graffiti.” By using different designs for the fill in, the same letters can feel completely different.

While studying at RISD, Kiselev switched majors. He couldn’t find a place where his training from graffiti connected to education. At one point, he realized that if he was to continue studying in a certain department, he would never be able to use his hands the way he wanted. It was too automated and too formulaic. He switched to fashion because it kept his hands busy with thread and had some autonomy. It was here he understood exactly how the philosophy around graffiti could morally better the fashion industry.

“From the beginning, graffiti rejected profit,” Kiselev says. Kiselev points out how the fashion world is full of trauma: labor exploitation in factories where workers don’t have water and the work is draining and monotonous. And fast fashion products are made to be thrown out and bought again. A pattern for instance (a design to cut and sew cloth) may be off and result in a thousand shirts that are wrong. Before the “off” shirts can leave the factory, they are burnt and the pattern is corrected. As an industry, fast-fashion is one of the world’s most potent emitters.

“People look at private spaces. They look at the Bronx vs. Manhattan, and they are not happy. In the Bronx, there’s a history of trauma. There’s police brutality and the youth who have to hide from cops. There’s the imprints of segregation and it’s still around and there’s the poverty that comes from all this. Graffiti, at its roots, is a nonviolent way for young people to express themselves against injustice. There’s this fake assumption in our society that money or power make you famous. In graffiti, you get to be famous based on where you write your name, and it doesn’t matter how much money you have,” Kiselev explained over-and-over to his grandmother, museum-goers, and New Yorkers, walking on the street. It took his grandmother ten years to understand what he was doing, but in the end, she found so much respect for his generation that she converted her peers into accepting graffiti.

There’s this false belief that patches are uncouth. They’re a sign a garment has lost its original form, and for this reason, it is impure and a new garment must be bought. If one looks closely at patch, it’s like a tattoo (it’s a permanent alteration of something’s nature and an act of self-expression). Metaphorically, these acts are repairs. Isn’t it better to know something’s been repaired and repaired often than to know it started off pristine?

Though many visitors of the Expressive Repair exhibit were new sewers and young sewers, they were all able to shape one-of-kind patches and stitch them with designs. They made a quilt, which is graffiti upon the fast-fashion world. Ironically, it is the pricey world of high fashion which covets the art of mending, draping, and repair as seen by the decrease in ateliers (in-house workrooms to make garments). It is a declining talent. It is the youth who can take back this skill, outline patches from scrap material, and fill them in with thick colorful thread.

Author

My background is in creative writing. I just graduated from Brown University in 2019 and have a degree in Literary Arts. I often sew objects for my stories in lieu of illustrating them. I am currently writing a non-fiction piece about a power outage that leads to a candle-lit dinner in Pune, India. I am also hoping to begin writing for the Center of Women and Entrepreneurship, a local non-profit that offers business courses and scholarships.

My background is in creative writing. I just graduated from Brown University in 2019 and have a degree in Literary Arts. I often sew objects for my stories in lieu of illustrating them. I am currently writing a non-fiction piece about a power outage that leads to a candle-lit dinner in Pune, India. I am also hoping to begin writing for the Center of Women and Entrepreneurship, a local non-profit that offers business courses and scholarships.