The Knot Garden

Wyth Flora paynted and wrought curyously,

In divers knottes of marvaylous gretenes;

Rampande lyons stode up wondersly,

Made all of herbes with dulcet swetenes,

Wyth many dragons of marvaylos likenes,

Of dyvers floures made ful craftely,

By Flora couloured wyth colours sundry.

Stephen Hawes, The Pastime of Pleasure, or The History of Graund Amoure and La Bel Pucell (London, 1509).

–&–&–&–

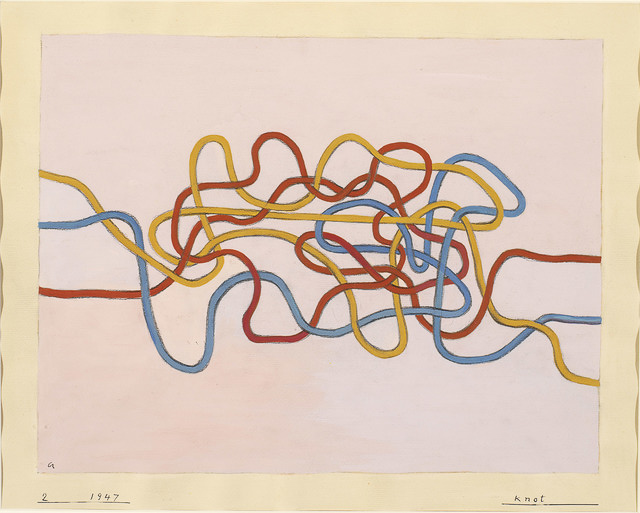

Knots are fastened loops of string, rope, or thread. Within craft, knotting is used to structure fabrics by looping, weaving, and intertwining multiple threads, forming an open fabric. Anthropologist Tim Ingold describes in poetic form how knots are the memoried elements of fabrics, of fibres “bound in sympathy”—meaning that they work together to create a “mesh of lines”. Following this, we can think of fabrics (and other knotted things) as archives that contain traces of their makers, their constitutive fibres, their shaping, and their particularity. A knot is a repository of making. And yet it can be undone, unmade. The knot might be lost, yet the memory of their making is retained. (Just think of the knots in Ariadne’s thread.) Textile designer and weaver Anni Albers understood this all too clearly. Her gouache drawings of knots show their ends to be “on the loose,” seeking out new forms, new relationships, all the while retaining their kinks and bends.

And it is this restlessness, this agitation of knots that earns their place “among the most ancient of human arts”. When seeking out the rationale for contemporary architecture, architectural theorist Gottfried Semper traced their movement from nets to woven textile hangings, and from there to enclosed spaces. The knot created surfaces, but also spaces. It slips and translates across materials, practices, and times.

And so to medieval English knot gardens with their criss-cross patterning of plants, as if formed by continuous threads. Rosemary, lavender, bee-flowers, hyssop, sage, thyme, cowslips, peony, daisies, pinks, southernwood, and Sweet Williams – planted out in a succession of continuous and interrupted lines to forming an embroidery-like pattern through a kind of illusion. George Cavendish described a spectacular garden at Hampton Court with “knotts so enknotted, it cannot be express”, untethered and over-run, a paradise of green and gold foliage.

–&–&–&–

Knots are distractions, entanglements, muddled encounters. They are “always in the midst of things, while their ends are on the loose, rooting for other lines to tangle with.” Knots can help us think about the proximity and potential togetherness of divergent ideas, thoughts, or practices – remarkable in their complexity.

Short bibliography

Anni Albers, On Weaving (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1965).

Alicia Amherst, A History of Gardening in England (London: Bernard Quaritch, 1895).

David Jacques, “The Compartiment System in Tudor England,” Garden History, Vol. 27, No. 1, Tudor Gardens (Summer, 1999), pp.32–53.

Tim Ingold, “Transformations of the Line: Traces, Threads and Surfaces,” Textile: Cloth and Culture, Vol. 8, Issue 1, 2010, pp.10–35.

Tim Ingold, The Life of Lines (Oxon: Taylor & Francis, 2015).

Gottfried Semper, The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings, trans. by Harry Francis Mallgrave and Michael Robinson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

–&–&–&–

Kimberley Chandler is a writer, researcher, editor, and designer with a PhD in Design and Architecture from the University of Brighton, UK.

–&–&–&–

Sky Series: Painting the heavens with glass - Zoë Veness employs an open cloisonné technique to make pendants that capture fleeting skies on Dharawl Country.

Sky Series: Painting the heavens with glass - Zoë Veness employs an open cloisonné technique to make pendants that capture fleeting skies on Dharawl Country. Korean Maedeup: A culture of knots - A recent exhibition at the Korean Cultural Centre Australia, in collaboration with the National Folk Museum of Korea, displayed the intricate beauty of knots.

Korean Maedeup: A culture of knots - A recent exhibition at the Korean Cultural Centre Australia, in collaboration with the National Folk Museum of Korea, displayed the intricate beauty of knots. Ropework: Soft garniture for life - Finn McCahon-Jones weaves a story around his artistic self, Finn Ferrier. An innocent exploration of knotting ends up as part of the treatment for a life-threatening illness.

Ropework: Soft garniture for life - Finn McCahon-Jones weaves a story around his artistic self, Finn Ferrier. An innocent exploration of knotting ends up as part of the treatment for a life-threatening illness. Embroidering pugholes - Sera Waters describes how her embroidery brings to the surface the holes dug during settlement that remained as wounds on the landscape.

Embroidering pugholes - Sera Waters describes how her embroidery brings to the surface the holes dug during settlement that remained as wounds on the landscape. Pamela Leung’s Red Line Story - Alma Studholme follows the red line and finds both hope and fear in an installation by Pamela Leung.

Pamela Leung’s Red Line Story - Alma Studholme follows the red line and finds both hope and fear in an installation by Pamela Leung. The Messenger Through The Twilight: A clay apocalypse - Raksit Panya introduces five Thai ceramic artists whose work foretells an archeology of the present.

The Messenger Through The Twilight: A clay apocalypse - Raksit Panya introduces five Thai ceramic artists whose work foretells an archeology of the present. Erroll Pires ✿ The master of ply-split braiding - Helen Ting and Khushbu Mathur ask Erroll Pires from Ahmedabad how a timeless textile technique became his life's work.

Erroll Pires ✿ The master of ply-split braiding - Helen Ting and Khushbu Mathur ask Erroll Pires from Ahmedabad how a timeless textile technique became his life's work. The Kaikai of Rapanui - Marcela Garrido Díaz shares a string figure from Rapa Nui, accompanied by its traditional chant.

The Kaikai of Rapanui - Marcela Garrido Díaz shares a string figure from Rapa Nui, accompanied by its traditional chant. Kyoko Hashimoto ✿ the Musubi necklace - Kyoko Hashimoto's Musubi necklace is a striking example of how a Japanese craft technique can help us appreciate the local quality of another country, in this case the sandstone that defines the Sydney basin.

Kyoko Hashimoto ✿ the Musubi necklace - Kyoko Hashimoto's Musubi necklace is a striking example of how a Japanese craft technique can help us appreciate the local quality of another country, in this case the sandstone that defines the Sydney basin. Nicole Robins ✿ It’s all in the loop - The Sydney exhibition Totes Serious…who made your bag features unique baskets from Nicole Robins, made from a common indoor plant.

Nicole Robins ✿ It’s all in the loop - The Sydney exhibition Totes Serious…who made your bag features unique baskets from Nicole Robins, made from a common indoor plant. Mikio Toki ✿ Edo kites keep hope afloat - Our pursuit of beautiful and thoughtful objects can take us far beyond the gallery. From kite-maker Mikio Toki, we learn that art taken to the skies can be a powerful way of giving thanks.

Mikio Toki ✿ Edo kites keep hope afloat - Our pursuit of beautiful and thoughtful objects can take us far beyond the gallery. From kite-maker Mikio Toki, we learn that art taken to the skies can be a powerful way of giving thanks. Shibari on the Strathbogie Ranges: The art of Japanese rock knotting - Anne Newton recounts how the Japanese technique of knotting rocks helped her express her appreciation of the Victorian highlands.

Shibari on the Strathbogie Ranges: The art of Japanese rock knotting - Anne Newton recounts how the Japanese technique of knotting rocks helped her express her appreciation of the Victorian highlands. 4,000-year-old string discovered in Egypt - At Garland, we love stories of string. This rich article from a publication about coastal cultures includes the story of how perfectly preserved papyrus rope was discovered in a man-made cave in the ancient Egyptian harbour of Saww. String-lovers will enjoy this.

4,000-year-old string discovered in Egypt - At Garland, we love stories of string. This rich article from a publication about coastal cultures includes the story of how perfectly preserved papyrus rope was discovered in a man-made cave in the ancient Egyptian harbour of Saww. String-lovers will enjoy this. Expanded lace: Lindy de Wijn at Bundoora Homestead - In an era of "expanded" art, we now find different textile crafts going beyond the traditional domestic setting to find a place in the world.

Expanded lace: Lindy de Wijn at Bundoora Homestead - In an era of "expanded" art, we now find different textile crafts going beyond the traditional domestic setting to find a place in the world.  Knotting culture: the muka of Rowan Panther - Tryphena Cracknell considers the way Rowan Panther has interpreted the traditional muka fibre within the technique of lace-making.

Knotting culture: the muka of Rowan Panther - Tryphena Cracknell considers the way Rowan Panther has interpreted the traditional muka fibre within the technique of lace-making. Knot Touch: From greenhouse to gallery - Jaqui Knowles explains the ways in which the NZ Maritime Museum has unraveled the potential of Jae Kang's tomato plant installation.

Knot Touch: From greenhouse to gallery - Jaqui Knowles explains the ways in which the NZ Maritime Museum has unraveled the potential of Jae Kang's tomato plant installation. Knot thinking: The Boorhaman residency - Chaco Kato describes the mental benefits of knotting that she discovered during her residency at Boorhaman.

Knot thinking: The Boorhaman residency - Chaco Kato describes the mental benefits of knotting that she discovered during her residency at Boorhaman.  String Figure Workshop – 2 October - Robyn McKenzie introduces the world of string figures that she has developed with Yolŋu collaborators. Learn about the meaning and making of string figures in the cosy space of Brunswick's yurt.

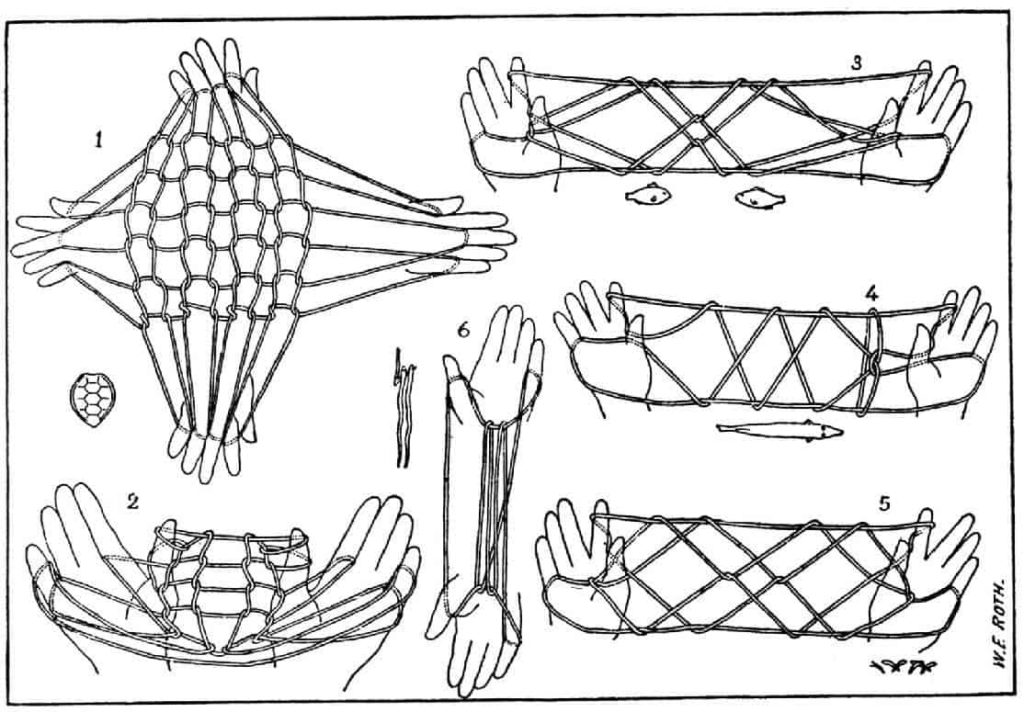

String Figure Workshop – 2 October - Robyn McKenzie introduces the world of string figures that she has developed with Yolŋu collaborators. Learn about the meaning and making of string figures in the cosy space of Brunswick's yurt. Quarterly Essay: Remembering the string figures of Yirrkala✿ - Robyn McKenzie discovers a mysterious trove of books about string figures. To understand their meaning today, she travels to Yirrkala and learns slowly how to create these figures for herself. But it is only by making them into a static art product, through printmaking, that she is able to engage the community. What unfolds is a revelation of thinking through string.

Quarterly Essay: Remembering the string figures of Yirrkala✿ - Robyn McKenzie discovers a mysterious trove of books about string figures. To understand their meaning today, she travels to Yirrkala and learns slowly how to create these figures for herself. But it is only by making them into a static art product, through printmaking, that she is able to engage the community. What unfolds is a revelation of thinking through string.