I.

In 2003, Māori novelist Witi Ihimaera credited Pākehā (European New Zealander) photographer Brian Brake with having “literally created the approach to photographing traditional Māori art”, and suggested that Brake “elevated representations of Māori art to another level”.[1] Brake’s success, wrote Ihimaera, was sustained by his recognition of the living nature of customary Māori art: “I believe that Brian saw what Māori saw: the living object, the wairua that all Māori know resides in wood, in greenstone, in whalebone, in bird feather.”[2]

Brake’s photographs of Māori art are indelibly associated with the exhibition Te Māori, which toured the United States in 1984 and 1985. This exhibition of customary or traditional Māori art has become a kind of shorthand term for the transformation of these objects from artefacts to art to taonga (treasured item, prized possession, valued person or thing). As Māori anthropologist Hirini Moko Mead wrote in the exhibition catalogue, taonga are objects of “immanent power, an object that has within it a hidden force.“[3] Te Māori, according to this view, was not “an exhibition of inanimate art objects” but rather of “taonga which contain immanent power and on which are pinned a host of powerful words.“[4]

Brake himself claimed that an awareness of this “immanent power’ was important to his photographic practice. As the Auckland Star newspaper reported, “alone with the various carvings of historic figures, Brake says he often felt a powerful presence conveyed by these carvings. . . . Aware that the artefacts being displayed in Te Māori are regarded as living treasures of the Māori culture, Brake says in trying to represent the objects as best he can in photographs, he is guided by the works themselves.”[5]

In 2011, Māori art historian Ngahuia Te Awekotuku suggested that the journey from darkness to the world of light, which structures Brake’s photographs, was a metaphor of the way these images collapse and overcome the distance between the taonga (many of which are held in museums, far from their descendants) and Māori audiences. As she wrote, “The objects selected all tell their own story with the eloquence and fluidity of mauri, their inner light, manipulated and drawn out, into the world of the living; and the living, nga uri whakatipu, the descendants, like me, respond to them, claim them back, celebrate their beauty and their power.”[6] She concluded her essay with a statement that raises some important questions of agency:

For Māori and all New Zealanders, Brian Brake has left an incomparable legacy; a means of seeing and responding to taonga beyond our reach, beyond our time. Kua oho ano te mauri – these taonga pulse or shimmer on each page. From within his designs of light and shadow, they move forward, they dance, they glow, they chant, and they threaten; perhaps that was not his intention at all! But perhaps it was theirs, hei oranga ngakau mo te iwi, hei hapai i nga uri whakatipu, a source of pride for the people, an inspiration for generations yet unborn . . .[7]

Here, agency is ascribed to the taonga themselves, rather than to Brake the photographer. There is a sense in which, despite Brake’s good intentions, taonga exceed his ability to represent them. Te Awekotuku leaves a productive doubt as to who is ultimately responsible for the success of these images; the power of the photographs is due as much to their subjects as to the photographer. These taonga act; they desire certain outcomes. It is as if they are hijacking Brake’s photography practice for their own ends.

II

From the late 1970s, Pākehā photographer Mark Adams has been seeking ways to represent the dynamics of Aotearoa New Zealand as a settler-colonial society. His photographs are always looking for Pākehā—an identity that, like all forms of politically dominant whiteness, operates successfully by remaining unseen or invisible.

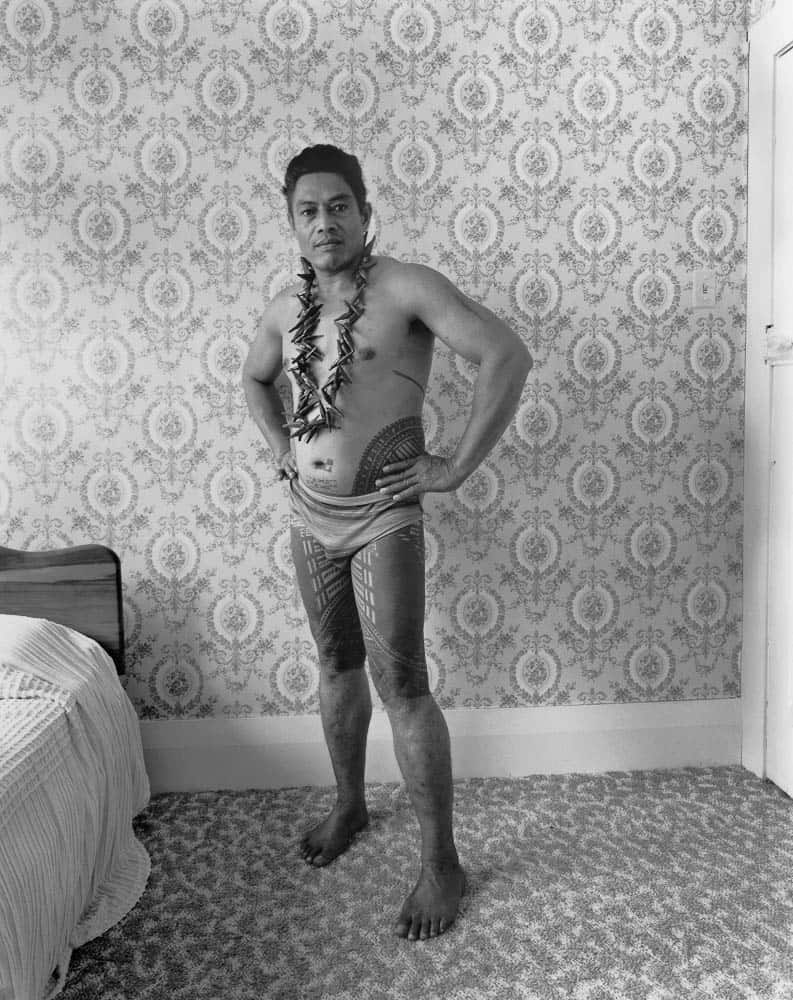

Mark Adams, 2.4.1978. Grey Lynn Auckland. Mr Salati Fiu. Tufuga tatatau. Fa’alavelave Petelo, gold toned silver bromide print, 610 x 508 mm, collection of the artist

Adams identifies his 1978 photograph of Mr Salati and his pe’a (tattoo) as a critical point in his practice. As he recalls:

What happened at that moment was complex and a bit confusing, but it is important because it inflected everything that happened from then on. It was the visual combination of pattern in the context of the interior and Mr Salati and his tattoo. It looked to me like an image—a powerful image which wasn’t easily accounted for. At one level I was thinking about my situation. The stranger in the frame was me, not him. He already knew he was in Polynesia. That was what I needed to know. Up to that moment that wasn’t exactly clear to me. What I saw at that moment was my position. I was the exotic in the frame, even though at that other level he and his fabulous tattoo were obviously exotic to me, as you would expect. Of course it’s more complicated than that, but that was my first reaction. I was thinking, is this Polynesia or is this New Zealand, or is it both simultaneously, or is it Polynesia on Sunday mornings, or what? And this all seemed contestable and unstable.[8]

In his photographs, Adams invites his settler viewers to ask: where am I in these images? To frame it in terms of local politics, Adams aims his camera at Pākehā by pointing it at Māori (and Pacific) subjects. In a settler society like Aotearoa, this is not a straightforward project, as settlers quite often dress up their claims to be indigenous (and thus push aside the original inhabitants of the land) through the appropriation of native art and cultural practices. The challenge is to find ways to make photographs that talk about, but don’t reinscribe, these dynamics.

Between 1978 and 1994, for example, Adams repeatedly photographed the Rotorua region of New Zealand, which became a tourist destination for Europeans in the nineteenth century, who were attracted by the scenic conjunction of geothermal activity and the indigenous Māori people and their art. When the government took control of the new township, local Māori suffered the loss of land and political autonomy, but they also skilfully used tourism to create dynamic new social and cultural practices that were vehicles for indigenous sovereignty. In Rotorua, Māori and Pākehā values clash in the landscape, or coalesce into surprising objects that register cross-cultural intimacies of various kinds.

Adams’s photographs offer no resolutions, only problems. They patiently track the material traces of various forces that coalesce in specific sites—whether the loaded landscapes of Dusky Bay, or the South Island, or the domestic spaces of a Grey Lynn villa, or the institutional spaces of a museum. They also productively grapple with time—the moment when the photograph was taken, but also a conception of the present as a porous entity that is affected by unexpected and uncontrolled leakages from the past.

III

Areta Wilkinson, 05 Series, 1996, pingao, harakeke kiekie, basalt, argillite, pounamu, kea and kererū feathers, pāua, bone, tōtara, 43 x 63 mm (each), Te Rūnanga o Ngai Tahu; Auckland Museum, 1996.215.8,

Māori contemporary jeweller Areta Wilkinson tackles the dynamics of settler-colonialism from the Indigenous side. She was one of the first graduates of the Craft Design courses set up in the 1980s to train studio craftspeople; and she was also part of a pioneering generation of Māori and Pacific jewellers who became active in the 1990s. The challenge in their work was to a previous Bone Stone Shell movement,[9] which adopted natural materials and references to Pacific and Māori art to make tribal jewellery for urban Pākehā. When a generation of Māori and Pacific jewellers came along, the awkward question arose: Who do big breastplates and hei tiki actually belong to? If those are Indigenous signs, then how can Pākehā use them to make themselves appear local?

In the later 1990s and early 2000s, Wilkinson’s jewellery was often focused on the museum as a system of conceptual and material practices that has separated taonga Māori from their descendants. The 05 Series is a good example: natural materials widely used in the production of customary Māori art are set within contemporary jewellery/western brooch forms. They each come with mock accession numbers and have the legend “do not touch” stamped on the back. But when they are assembled as a group, they form an image of Aoraki (Mt Cook), an important ancestor of Kai Tahu, Wilkinson’s own iwi (tribal group). The work becomes a form of pepeha (a way of introducing yourself), a fabricated and materialised statement of identity.

Since 2010, Wilkinson has begun operating differently. The shift might be described as the difference between working as a Māori contemporary jeweller, and a Kai Tahu contemporary jeweller. (Kai Tahu is an iwi from the southern part of Aotearoa New Zealand.) That is a subtle but important difference. The first is about Māori as a group in opposition to settler society and colonialism, as the Indigenous people of Aotearoa, in solidarity with other Indigenous peoples who are also still oppressed; the second is about being the Indigenous people of a specific place, and remembering the stories, sayings and histories that anchor you to these specific locations. Her new work doesn’t fit within the established categories of Māori adornment, but draws on the materials and traditions of contemporary jewellery to make objects that reflect Kai Tahu ideas about the world, the body and identity. One way to do this is to suggest that jewellery is just like pepeha, pithy phrases or sayings that reflect tribal history and belonging. Wilkinson takes the concern with identity and emblems that has been a major part of contemporary jewellery in Aotearoa, and pushes it in new directions, renovating it with a new politics.

IV

- Areta Wilkinson and Mark Adams, MAA Cambridge. Cheviot Hills Tiki. From Julius Von Haast Canterbury Museum, 2010, cyanotype blueprint, 340 x 287 x 35 mm (framed), collection of the artists

- Areta Wilkinson and Mark Adams, VI 29337. Tangiwai. Museen Dahlem Sudsee Store, 2016, silver bromide print, 360 x 285 mm, collection of the artists

- Mark Adams, Areta Wilkinson, Julie Adams making photograms. Museen Dahlem Sudsee Store, Berlin, 2015

The first photogram made by Adams and Wilkinson was, in fact, the outcome of chance, an unplanned opportunity. Both artists were in residence at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge. Wilkinson’s project had brought her and Adams to various wearable taonga in the museum’s collection. They were photographing them in a manner that was an awkward hybrid of Adams’s postcolonial attention to the museum environment as part of the composition, and Wilkinson’s approach as a contemporary jeweller with a firm interest in the relationship between the object and the body, and a particular concern with the physical connection between taonga and their descendants. Think hands cupping the taonga, or holding them in place in front of the body. Despite being well-meaning, they were not great images.

The museum’s photography curator, Jocelyne Dudding, had some blueprint photographic paper in her office, which she had been playing around with. Adams co-opted a sheet, laid a hei tiki from Cheviot Hill in the South Island on top of it, and exposed it to light. The result was, for both artists, something remarkable. For Adams, it was another encounter with a powerful image whose effects he could not easily account for. The photogram offered something visually striking, exactly the quality he had been seeking in the other, unsuccessful photographs, but it also seemed to extend his project to find ways to engage with taonga without, as he puts it, messing around with them. For Wilkinson, the recognition that the photogram was a successful work of art was matched by her identification of the void or shadow of the hei tiki as precisely the conceptual space she had been looking for, which would allow her to make new work in dialogue with customary models but maintain her status as a contemporary practitioner.

In the six years since this technical and conceptual discovery, Adams and Wilkinson have continued to make photograms of wearable taonga provenanced to Te Waipounamu, the South Island. These have come from museum collections in Aotearoa and overseas. The technique has been refined: silver bromide paper has joined blueprint paper; and Adams has become more adept at bouncing light underneath individual taonga to play with the illusion of dimensionality. There has also been a shift in subject, as wearable taonga have been joined by the tools used to make them, and the materials from which they are carved, such as a collection of moa bones from a midden in the South Island.

There are a number of forms of agency at work in these camera-less photographs. The photogram seems tailor-made to respect and assert the agency of the taonga who are represented using this technology. Photography is peculiar in the way it hands over its representational capacity to what is being represented. This is especially foregrounded in camera-less photographs. As Australian art historian Geoffrey Batchen writes, “The things we see . . . seem to have imprinted themselves on the paper before us: directly, physically, causally, without mediation, at one-to-one scale. For this reason, to make a photograph without a camera is to privilege photography’s indexical capacities over all others.“[10] Photograms promise to get us closer to the presence of things, and “to fulfil a desire that lurks within all acts of representation: to collapse the boundary between absence and presence, between an image and what it’s of, between that image and its process of production.”[11]

In other words, these photograms are the perfect technology to register the agency of taonga as actors in their own representation. Circulating around the photographs of Brian Brake, for example, are various intimations that taonga are at work in the end result, co-producers of their own image and able to exceed what Brake achieves; to exceed, if we are critical, the primitivising frame that he applies with his camera and lighting. In these photograms by Adams and Wilkinson, taonga literally imprint themselves on the paper. A camera-less photograph is not just of something; it is something—in this case, the taonga themselves. Photograms are an emanation of the world, rather than a copy, and the division between reality and its representation becomes permeable, folding one into the other. In this sense, they are an experience of the impossible.[12] This parallels the nature of taonga as objects that exceed the material world and reach into spiritual or metaphysical realms; from a Pākehā perspective, taonga are able to perform impossible tasks, suturing time in unusual ways, and dissolving the division between subject and object.

The photograms also enable certain possibilities within Adams and Wilkinson’s respective artistic projects. These are one-off images made by placing taonga on photographic paper and exposing them to light. The photograms are representations—Wilkinson calls them “shadows”—of taonga, not the taonga themselves, so there is some distance between the image and the original; but these images are also singular, not multiple, and they require the indexical trace of the taonga to exist. They are like avatars of the taonga, moving out into the world in ways that the taonga cannot, sharing their qualities but also attaining a kind of uniqueness and independence from the taonga involved in their creation.

Ultimately, this is a respectful, honest and radical way for these two artists to interact with taonga that, importantly, makes no claims that can’t be sustained. It is an approach that is calibrated according to the questions that Adams, a Pākehā photographer, has been asking in his work, specifically around the appropriate ways to represent Māori art, and what a decolonising Pākehā artistic practice might look like. It also represents a shift, beyond the postcolonial strategy of embedding objects in their environments, to include within the frame those details that most sharply and troublingly indicate the histories and politics that animate life in Aotearoa. And it is an approach calibrated according to the questions that Wilkinson, a Māori jeweller, has been asking in her work, specifically around the best way to engage with customary art as a contemporary practitioner and having your practice intimately shaped by what comes before—made, in fact, in the likeness of nga taonga tuku iho, the taonga handed down from the ancestors, but clearly oriented to the present and future.

Finally, I want to propose that the photograms enable another kind of agency that concerns potential futures. As a society, we are entering into a post-Treaty settlement era, one that requires, as Māori academic and musician Charles Royal puts it, a “creative tino rangatiratanga” (sovereignty, self-determination) that will adjust Māori identities and cultural practices to the opportunities that exist beyond grievance and the painful struggle for redress that have been a primary focus of Māori communities since Pākehā began breaking the terms of the Treaty of Waitangi only a few years after it was signed in 1840. To put this in context, Kai Tahu signed their Treaty settlement in 1996, which means they have been operating in a post-Treaty settlement environment for two decades. It has involved control of significant legal, cultural and financial resources to determine what being Kai Tahu means in the twenty-first century. But just as Māori now have the opportunity to reinvent themselves, so Pākehā will also have to find new identities and cultural practices in the coming years that can meet Māori as respectful partners in the imagination of a new Aotearoa. As has always been the case because of the tense intimacy between Māori and Pākehā, when Māori identities shift, Pākehā identities also transform. Both Wilkinson (as a member of Kai Tahu) and Adams (as a long-time collaborator with Kai Tahu historians) have been shaped by these particular dynamics.

These photograms are co-authored works of art, a result of a Pākehā photographer and a Māori jeweller collaboratively looking at taonga from Te Waipounamu, and finding a form of art making that offers shared territory. In the multiple agencies that assert themselves in these objects, might there be a glimpse of what a post-Treaty settlement artistic practice actually looks like? The question that is perhaps most interesting – are these photograms Māori art, or not? – feels interestingly transgressive because it is generated by conditions quite different to the dynamics of the 1980s and 1990s that underpinned the cultural appropriation debate. In these photograms, for example, there is no need to assert the agency of taonga against the role of the Pākehā photographer, as becomes necessary in Brake’s practice. In the photograms of Adams and Wilkinson, there are no answers, but a tantalising glimpse of artworks that respect the taonga Māori who made them, but also emerge from a dual whakapapa (genealogy, a system of understanding relationships between people, and people and the natural world) of Pākehā and Māori artistic practice.

Notes

[1] Witi Ihimaera, Māori Art: The Photography of Brian Brake, Reed, Auckland, 2003, p10.

[2] As above, p 11.

[3] Hirini Moko Mead, “Nga timunga me nga paringa o te mana Māori: The Ebb and Flow of Mana Māori and the Changing Context of Māori Art’ in Sydney Moko Mead (ed), Te Māori: Māori Art from New Zealand Collections, Heinemann & The American Federation of the Arts, Auckland, 1984, p 22.

[4] As above, p 23.

[5] “Widening the Audience’, Auckland Star, 17 Apr 1984, section 2, p 6.

[6] Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, “Introduction’ in Māori Art: The Photography of Brian Brake, Raupo, Auckland, 2011, p 9.

[7] As above, pp 10–11.

[8] ““An Uncomfortable Edge”: A Conversation between Mark Adams and Nicholas Thomas March–April 2005’ in Sean Mallon, Peter Brunt and Nicholas Thomas, Tatau: Photographs by Mark Adams, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2010, p 66.

[9] The Bone Stone Shell movement refers to a period in New Zealand contemporary jewellery when a number of makers adopted natural materials (especially paua shell, pounamu and bone) in their work, and made stylistic references to Māori and Pacific adornment traditions. The movement takes its name from the Bone Stone Shell: New Jewellery New Zealand exhibition of 1988, which travelled to Australia and Asia. (For more information, see chapter 5 in Damian Skinner and Kevin Murray, A History of Contemporary Jewellery in Australia and New Zealand: Place and Adornment. Auckland: David Bateman, 2014, pp.118-149.

[10] Geoffrey Batchen, Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery and DelMonico Books, New Plymouth and Munich, 2016, p 46.

[11] As above, p 46.

[12] As above, p 47.

Author

Damian Skinner is a Pākehā art historian and curator. He is currently the 2017 J D Stout Fellow at the Stout Research Centre, Victoria University of Wellington, where he is completing a biography of artist Theo Schoon.

Damian Skinner is a Pākehā art historian and curator. He is currently the 2017 J D Stout Fellow at the Stout Research Centre, Victoria University of Wellington, where he is completing a biography of artist Theo Schoon.